|

Hello Friends and Readers

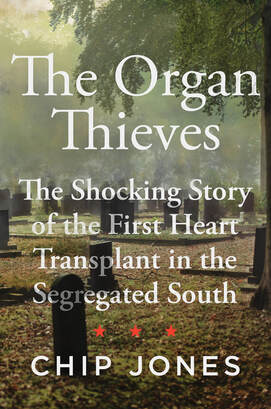

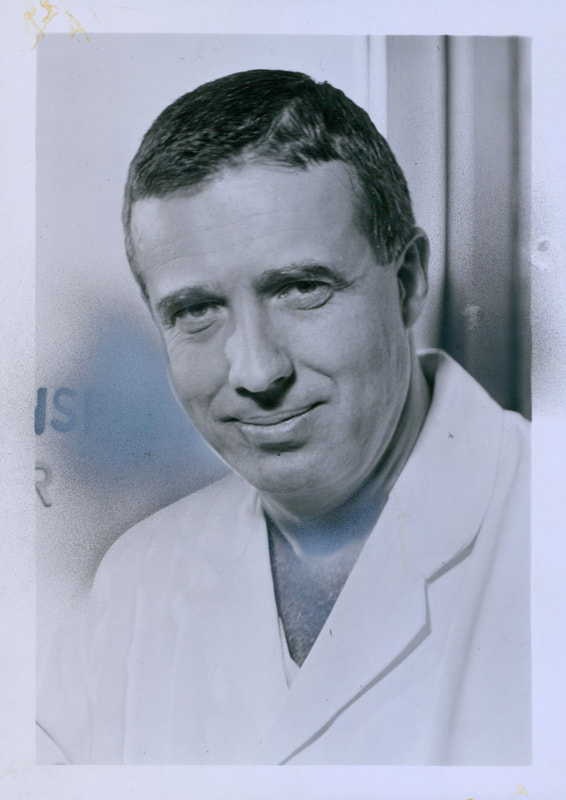

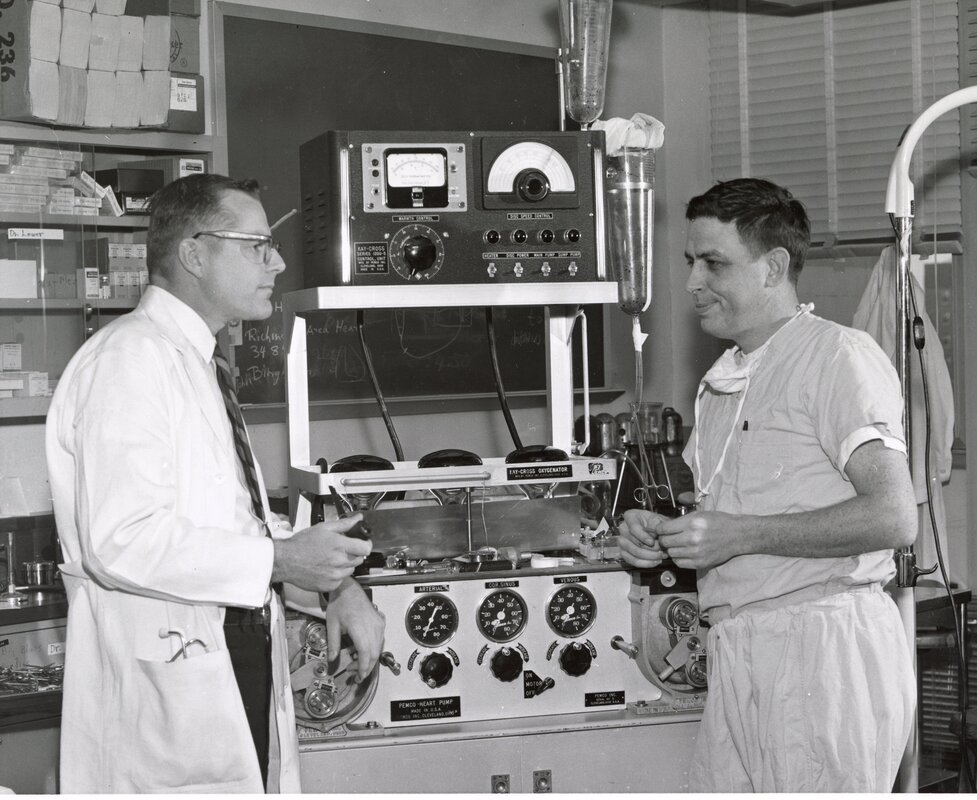

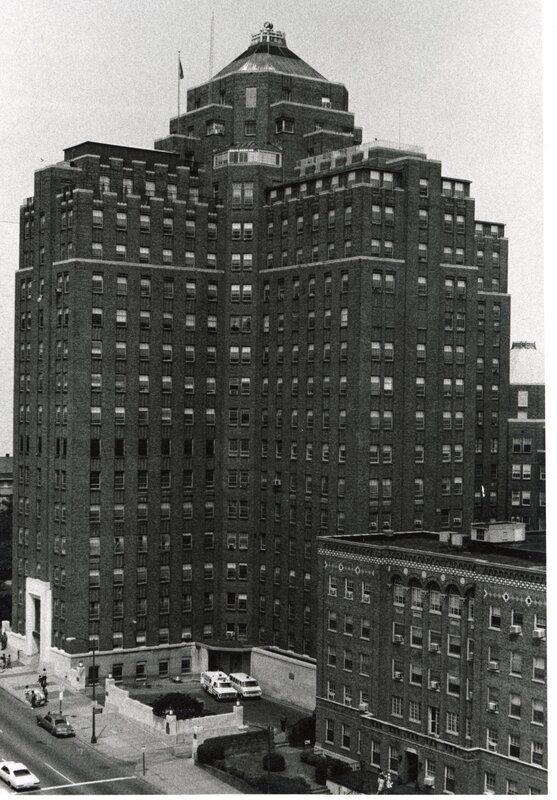

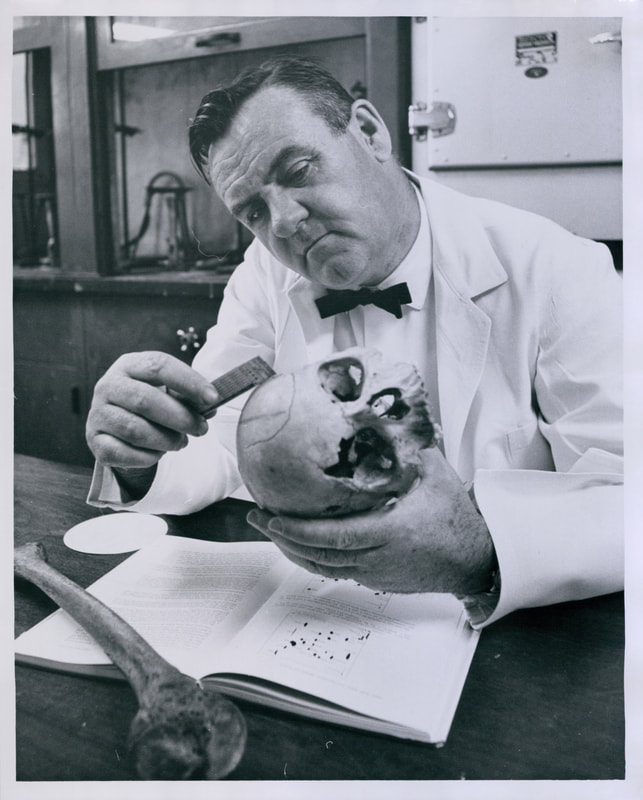

My work on The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South started several years ago after I read about the work of two medical pioneers in kidney and heart transplantation, David Hume and Richard Lower. These legendary surgeons once practiced medicine in the city where I’ve worked as a newspaper reporter, magazine editor, and in other communication posts: Richmond, Virginia. When I heard that this dynamic duo at the Medical College of Virginia had trained the doctor who ultimately performed the world’s first successful human heart transplant in late 1967 – Dr. Christiaan Barnard of South Africa – I began to probe the events of May 25, 1968. That was the day Lower and Hume conducted their own historic operation – the first heart transplant in Virginia and sixteenth in the world. |

Order now

|

|

As a veteran newsman who spent five straight years writing investigative articles shedding light on the secrets of Richmond’s tobacco giant, Philip Morris, I’ve always been intrigued by what happens when large institutions make decisions that affect average people. I soon noticed something missing in MCV’s early version of the story of its memorable transplant: the identity of the man who had given up the heart transplanted into the body of an ailing Virginia businessman. Who was he and why was his name left out of the earliest accounts of the operation?

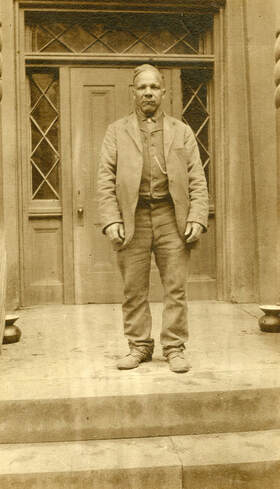

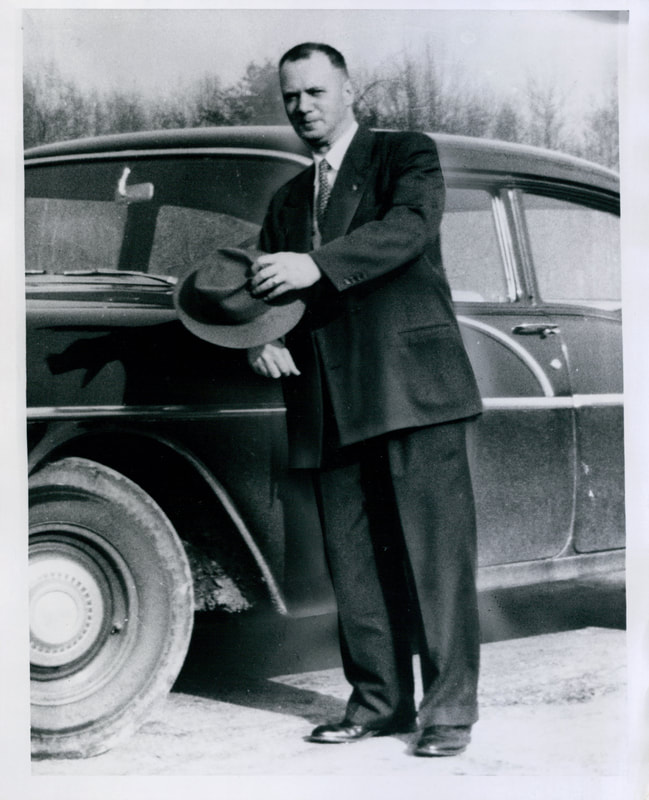

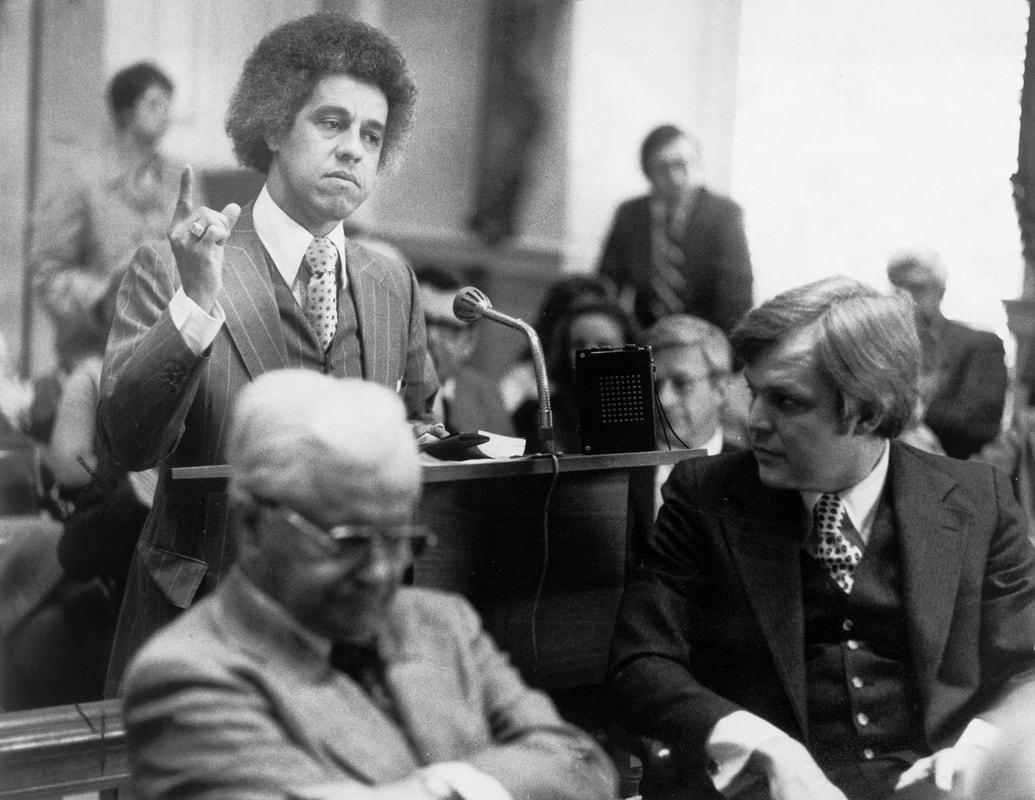

Back in 1968, Bruce Tucker’s name finally was revealed through the dogged reporting of local science writer Beverley “Bev” Orndorff, who later became my colleague at the Richmond Times-Dispatch. As I read Bev’s early articles and MCV’s news releases of the day, I kept wondering about the early omission of Tucker’s name. That led to other questions and revelations. For example, after the transplant and Bruce Tucker’s death, his brother, William, contacted L. Douglas Wilder, a successful young black attorney. He began to investigate the circumstances of the death and considered taking legal action on the family’s behalf. Wilder would go on to become the first elected African American governor in the nation’s history. During the three years of research and writing that went into The Organ Thieves, I kept discovering other pieces of a growing puzzle. Among them:

|

Moving forward, I revisited the strange series of events in 1994 when MCV’s past literally poked up through the mud. Construction workers were horrified to find skeletons and even human flesh in a well used as a “bone pit” below what is now the front entrance to the Kontos medical building.

Thankfully, today in Richmond, a joint public/private effort is underway to study and honor the lives of enslaved Americans whose bodies were stolen and dumped by the medical college in the 19th century. The effort is bearing fruit. I hope that The Organ Thieves helps inform such vital conversations to address the disturbing issues of the past that still trouble our nation.

Thankfully, today in Richmond, a joint public/private effort is underway to study and honor the lives of enslaved Americans whose bodies were stolen and dumped by the medical college in the 19th century. The effort is bearing fruit. I hope that The Organ Thieves helps inform such vital conversations to address the disturbing issues of the past that still trouble our nation.

“In this captivating true story, journalist Chip Jones outlines how ambitious surgeons took a black man’s heart without his family’s consent and implanted it into a white man’s body in the name of scientific progress. The Organ Thieves is a gripping exposé unveiling racism at the heart of medical advances.”

—Kristen Green, nationally bestselling author of Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights Battle

—Kristen Green, nationally bestselling author of Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights Battle

"In this doggedly reported account, journalist Jones (War Shots) reveals unexpected links between racial inequality and the race to perform Virginia’s first human-to-human heart transplant. On a Friday evening in 1968, African American laborer Bruce Tucker suffered a severe head injury. Taken to a Richmond hospital, he was pronounced dead the next afternoon. Without the knowledge or permission of Tucker’s family, a team led by cardiac surgeon Richard Lower transplanted Tucker’s heart into a white businessman, who initially recovered from the operation but died a week later. Informed by a funeral director that his brother’s heart and kidneys were missing, William Tucker hired lawyer (and future Virginia governor) Doug Wilder to look into the matter. Lower and the other surgeons were eventually cleared in a wrongful death lawsuit, though jurors intended to find the hospital negligent for allowing the procedure to go forward without consent from Tucker’s next of kin, and were only prevented by a statute of limitations. Jones connects the case to the long and sordid history of medical experimentation on African Americans, including the 19th-century practice of procuring medical cadavers from black cemeteries, and explores the tangle of ethical and legal questions around the concept of “brain death.” The result is a dramatic and fine-grained exposé of the mistreatment of black Americans by the country’s white medical establishment." --Publishers Weekly