|

I'm honored to be appearing next Monday, May 10 at 6:30 p.m. at a public zoom event: The Oliver Hill Book Club. Click here to register! Sponsored by the Richmond Public Law Library, this one-hour event is named in honor of Oliver W. Hill (1907-2007), a Richmond African American attorney and Civil Rights activist. Mr. Hill helped win the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court Case -- Brown v. Board of Education -- that led to the end of the doctrine of "separate but equal" in public schools.

Opinion: It was a long journey to get my coronavirus vaccine. It was worth the wait.

Opinion by Chip Jones The Washington Post, April 11, 2021 Metro/'Local Opinions" page C4: Chip Jones is a Richmond-based writer and author of “The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South.” When my bedroom phone rang early one recent Saturday morning, my natural inclination was to ignore it. Nothing good ever comes on the landline — even during the long wait for a coronavirus vaccine. My wife and I had been signed up for weeks to get our shots through the Virginia Health Department, CVS, Kroger and so on. Our early efforts led to one invite from our home county, Henrico, that was actually meant for police, firefighters and other first responders. “Whoops!” Henrico officials said in apologetic emails and news releases to thousands of disappointed citizens, including us. False alarms about vaccines spread with viral intensity along our usually sedate suburban street. Drive down to Newport News or Roanoke, friends and neighbors said . . . or maybe Clarksville, wherever that is. My wife and I started Googling. We weren’t getting our shots, but we were receiving real-time geography lessons. Eventually, though, all these “leads” started to take an emotional toll, not to mention cause sleep deprivation. Now, I say this as a 68-year-old man with no underlying conditions and who’s blessed with good health benefits. I face none of the well-documented struggles of health-care providers, teachers and others in the public sphere who should have been at the front of the vaccination line all along. So how did so many other people get theirs first? This undeniable example of class and White privilege led to our decision not to travel out of the area to get a shot at some distant CVS pharmacy — whether it was east to Newport News, south to Clarksville near the North Carolina line, west to Charlottesville, or even as far away as Abingdon in far Southwest Virginia. We would stay in place and wait our turn. That’s why weeks later, when that Saturday phone call came, I tried to go back to sleep. My cellphone downstairs started rocking out. I had to go get it. “Dad!” It was my very thoughtful daughter calling via Skype from abroad. “It’s opening up now. You have to try CVS!” “Okay!” I said, wishing for a strong cup of coffee to match her intensity level. “We’ll check it out.” “We” actually meant my wife, Debbie. She was the one who’d been putting in the most time checking the CVS website morning, noon and night. Rubbing sleep out of her eyes, she opened her iPad and set to work. She started by checking the site, but after typing in her age, and Zip code, and entering a date for a shot, there was no response. Even though all of the drugstores’ locations looked open across the state, nothing was coming up. Taking another tack, Debbie dialed an 888 number and said “agent.” Finally, after so many weeks of silence and frustration, someone answered her call. “Good morning!” she said. Soon she was engaged in a constructive chat with a young man who told her that, for him, it was the middle of the night. He was working from home. This led to some comic moments, such as when he said, “Sorry, ma’am, my dog’s barking. Could you please repeat your numbers?” Soon they were buzzing through a long registration form, easily overcoming any problems caused by distance or language. Within 30 minutes, Debbie was assigned to a random location and her appointment times were coming in via text and email. After more form-filling, my information arrived as well. “Thank you,” she told our distant deliverer. “Have a good night.” “You too, ma’am,” he said. But there was a catch. We had to head out of town to the arbitrarily chosen pharmacy site, some 100 miles to the northwest in Gainesville. After spending more time on Google Maps, a few days later we were cruising along what we call the back way to Dulles International Airport: Get off Interstate 95, take a deep breath of relief, then drive up U.S. 17 through the farms and bedroom communities of Fauquier County. Some time later, we pulled up to a very large CVS. A group of baby boomers was lining up as though Jimmy Buffett tickets were going on sale. Once Debbie’s phone app gave her a 15-minute notice, she was allowed inside. And because everything was running on time, I got in, too, well before my later appointment. As we answered questions and rolled up our sleeves, two young, cordial pharmacists shared their stories of driving around Virginia this past winter helping fight the viral scourge. As it had with us, covid-19 had taken them out of their comfort zones, visiting new places in the mountainous regions around Woodstock and Harrisonburg, helping vulnerable people in nursing homes. As I maintained my end of the conversation — no doubt from nervousness — I mentioned the fact that I didn’t plan to go inside to my church for Easter Sunday services, even if the church reopened by then. “I hope we have outdoor services.” My pharmacist, who wore a hijab, nodded and said she’d been thinking along the same lines. “We may have services outside our mosque.” I shut my eyes and waited for the prick of a needle. But there wasn’t one. “All done!” she said brightly. For a moment in this troubled time, I actually felt protected — not only by the brilliant scientists who developed the Moderna vaccine, but by this gentle caregiver. It was worth the wait. South Florida PBS recently shared its broadcast of a very fine book show, "Between the Covers." It's hosted by Ann Bocock, a former broadcast journalist in Richmond, who said she was surprised by the many things she learned about Virginia's capital in The Organ Thieves.

Also, if you missed the VCU Libraries Public Zoom event, here it is. Enjoy the great insights shared by VCU medical archivist Jodi Koste, as well as some thoughtful and provocative questions from many of you! Thanks to everyone who tuned in. Finally, here's a very well-done piece in VCU's student newspaper, The Commonwealth Times, by Anya Sczerzenie, including my push for a public apology from the university about its historical amnesia regarding Bruce Tucker.  Hi everyone! I'm honored to be on a Live Zoom event that starts at 10:30 a.m. this Thursday, Feb. 25. Sponsored by VCU Libraries, I'll be joined by Jodi L. Koste, Archivist and Head of the VCU Health Sciences and Library Special Collections and Archives. We'll focus on how her Archives (and other VCU library resources) aided my quest to understand the "heart transplant race" of the 1960s and the first such operation at the old Medical College of Virginia. As some of you know, Jodi's expertise and guidance were invaluable to the three years' worth of research and writing that became The Organ Thieves. Click here to receive a link to join the sessions via the VCU Libraries Development Office. OPINION: Unsettled History It’s time for VCU Health and the university to provide restorative justice regarding the story of its first heart transplant. (from STYLE WEEKLY, January 27, 2021)

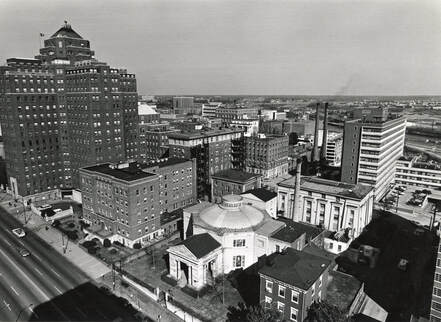

BY CHIP JONES There’s no way to put a price on the beating heart taken from a Black laborer in 1968 by white surgeons seeking professional fame and fortune. But it is possible for the state of Virginia to say his name – Bruce Tucker – and to honor his major contribution to medical history. While they’re at it, officials at Virginia Commonwealth University, where this ghoulish operation was long revered, should publicly apologize to Tucker’s descendants who still live in the area. Even as today’s doctors at VCU Health reportedly are trying to ease fears of the COVID-19 vaccine among Black Richmonders, they’d do well to treat this festering sore of history, one that adds to the litany of past national disgraces such as the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and the secret harvesting of Henrietta Lacks’ cervical cells. Closer to home, the death of Bruce Tucker provides a modern corollary to the Medical College of Virginia’s dark, dystopian origin story. As I learned from the university’s experts and its archives, the medical school’s founders paid grave robbers to pillage nearby cemeteries with the help of ambitious young medical school residents through much of the 19th century. These unspeakable practices – stealing human remains to supply cadavers for dissection – continued until the dawn of the 20th century. Some of these remains were exposed in 1994 when construction workers dug up an abandoned well. After VCU’s leadership ordered this archeological site to be covered over, an untold number of these human artifacts were left behind. Today, experts say, they’re under the front plaza of the Hermes A. Kontos Medical Sciences Building at 1217 E. Marshall St. After last summer’s release of my book, “The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South,” Edward L. Ayers, the noted historian and former president of the University of Richmond, said the book “speaks directly to the dilemmas of the twenty-first century.” A Washington Post reviewer agreed, saying that while “the abuses it records are decades old … the gruesome disregard for Black lives makes it an urgently modern warning.” Other scholars and reviewers from Dublin to Dallas to New York expressed similar views. But to date, this warning hasn’t been fully heeded at the scene of the Tucker tragedy -- VCU Health. In case his story is new to you, here’s a snapshot: On a Friday afternoon after work on May 24, 1968, Bruce Tucker was passing a bottle and talking with friends on Church Hill. Around 3 p.m., he tumbled off a wall, hitting his head. He was rushed down to the Medical College of Virginia. Despite suffering a severe head injury, Tucker’s heart remained strong – a fact duly noted by surgeons. By the next morning, the ailing Black man was identified as a potential heart donor even though he’d never asked to be one. Within hours, MCV’s top transplant surgeons persuaded a junior medical examiner to let them cut out Tucker’s heart – despite the fact that they’d failed to locate anyone from his family to give them permission. As the minutes ticked by, the surgeons – eager to execute their first heart transplant – and the medical examiner ignored Virginia’s Unclaimed Bodies Act. This law provided a 24-hour waiting period from the time a person was declared dead to when the body could be used for research. Though they argued that Tucker’s brain had ceased functioning, that was just their opinion. For you see, in 1968 Virginia had no legal provisions for doctors to declare anyone “brain dead.” But the headlines said otherwise. “Heart Transplant Operation Performed Here by MCV,” trumpeted the Richmond Times-Dispatch on Sunday, May 26, 1968. The same triumphant message was repeated until recently whenever MCV touted its well-respected organ transplant programs. It wasn’t until last summer, when word of my pending book got out, that the MCV Foundation attached an online editor’s note expressing “regret” over what it called “the controversy surrounding the lack of consent from Bruce Tucker’s next of kin before his heart was used in the first heart transplant performed at MCV.” The foundation also vowed “to listen and accept criticism and to learn from our past.” For Bruce Tucker and his surviving family members, it’s time for VCU Health and the university to provide restorative justice. First, university President Michael Rao – who’s led commendable efforts to remove Confederate-era names from buildings and plaques on campus – should take a shovel and dig up a plaque at the entrance of West Hospital at 1200 E. Broad St. that proudly proclaims, “Birthplace of Cardiac Transplantation” Why? Because there’s no mention of the Black man who died to make this birthplace happen! Next, rename the heart transplant program after Bruce Tucker and award scholarships in his name to students from Dinwiddie County, where Tucker’s descendants still live. Finally, some have suggested financial reparations are in order since not a penny was awarded to the Tuckers by an all-white jury in 1972. VCU’s Board of Visitors would do well to study a 2007 resolution passed by unanimous vote of Virginia’s General Assembly. This marked the first apology for the state’s role in promoting the slave trade since English settlers arrived in Jamestown in 1607. By taking such relatively small steps, the taxpayer-supported health system in Virginia’s capital can go beyond paying mere lip service and actually demonstrate that it’s learning from past mistakes. As President Joe Biden proclaimed in his inaugural address, “Don’t tell me things can’t change.” Chip Jones is author of “The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South.” He can be reached at [email protected] or his website, chipjonesbooks.com.  Sandy Hausman Sandy Hausman In this season of sacrifice and light, I appreciate the many keen insights sent to me by readers of The Organ Thieves. I’m especially struck by your continued calls for honoring Bruce Tucker’s contributions to medical science as well as the sacrifices made by his family to this day. I’m also grateful to Sandy Hausman, the award-winning correspondent for Virginia Public Media, for her recent report on Radio IQ/WVTF. Here’s an excerpt: “The medical college, now known as VCU Health, has quietly expressed regret over the controversy surrounding the lack of consent from Bruce Tucker’s family before his heart was donated to an ailing white businessman who died a few days later. In a university magazine, VCU says the story ‘underscores the need to listen to and accept criticism and to learn from our past as we work to honor the dignity of all whom we serve.’ “But Chip Jones wonders if that's enough – especially in light of another discovery. "In 1994, a huge construction project on the campus ground to a halt when construction workers were horrified to see human arms sticking out of the mud," he recalls. "Police called the university archaeology department, and they began to find bodies that were in a nearby well that had been dumped some time in the past. The remains were likely those of slaves or poor black residents of Richmond whose bodies were stolen from graves so medical students could dissect and study them.” “The Organ Thieves has won considerable attention from news organizations nationwide as America grapples with questions of systemic racism. “‘I love a quote from Richard Rohr, the theologian,’” [says Jones]. ‘You cannot heal what you do not acknowledge.’ I think there [are] still a lot of unacknowledged wounds that need to be healed.’" “The book includes a teaching guide, and Jones hopes it can be used in high schools to explore issues of race and healing with the next generation.”  As we enter the holidays, I hope everyone’s staying safe and healthy! Some readers have asked about getting an audio version of The Organ Thieves, so here’s a link to purchasing it and hearing a sample by the gifted reader JD Jackson. The Organ Thieves has received a major endorsement in the December issue of Scientific American. The review by editor Andrea Gawrylewski begins by noting America’s poor track record when it comes to providing equitable health care for Black Americans. “The roots of this inequity are firmly rooted in racism, not race, writer Jones shows in this gripping book,” she writes. Interest continues to spread across various media outlets, which you can see here at Media/Clips. These include a live stream interview on “Between the Covers” with Ann Bocock of South Florida PBS (the segment is slated for broadcast in early 2021, with possible national PBS broadcast). You can also hear a fine interview by Julie Rose on “Top of Mind” on BYU Radio. And Brian Ellis, an MFA student at Hollins University, just interviewed me for the university’s Jackson Center for Creative Writing. Click here! Readers continue to amaze and educate me about their own experiences. With his approval, I’m sharing one man’s poignant recollection about growing up in a Black family in rural Virginia in the 1950s. Reading The Organ Thieves brought back memories of his parents quietly discussing the treatment of African Americans in Virginia. “We were always told to go outside or leave the room when they talked about things like that,” he wrote me. “What I remember them discussing was that there were some experiments relating to body parts and cadavers at MCV.” In the 1950s, he noted, “Blacks were encouraged to use the Black hospital, Richmond Community. We lived in the town of Bowling Green that had a Black doctor who used Richmond Community. As I remember, he also referred patients to the Fredericksburg hospital as well as Howard University’s Freedmen’s Hospital.” His father often traveled on business in and around Bowling Green, the county seat of Caroline County, 42 miles north of Richmond. “He occasionally mentioned that he had been told of grave robbers. Since I was young, it did not particularly interest me. I thought the robbers were after valuables, such as bracelets, rings, and gold. Not bodies!”  Thanks to everyone for your thought provoking, inspiring, and engaging remarks about The Organ Thieves. As readers contact me from across the U.S. and abroad, I hope to share some of them. So far, you’ve addressed a number of intriguing topics – from the treatment of Black patients at the old Medical College of Virginia in the 1960s to the systemic racism of early American medical education. Many of you have said the book has helped expand your historical horizons during this year of national reckoning. Feel free to send me more thoughts about how the book has affected you, and, if possible, let me know if you’re OK with me sharing them on this blog (including whether or not you’d like your name to be used). Meanwhile, I’ll keep you posted on other book-related developments, including ways to honor the memory of Bruce Tucker and his descendants. In this first round of reflections, we start with two retired doctors who studied at MCV in the 1960s-1970s. Both vividly recall their time with the two star surgeons profiled in the book, Dr. David Hume and Dr. Richard Lower. “I was an ob-gyn resident at MCV in 1971,” wrote Dr. Bruce Bernie of Charleston, South Carolina, “and started med school at MCV in 1968. Your book was phenomenal and brought back rather bittersweet memories of my training.” Dr. Bernie noted Hume’s “high intensity” personality (along with some other choice words). Still, he found him to be a “great teacher.” Overall, though, he said, “My experience at MCV was an environment of anti-Semitism, homophobia, and outright racial prejudice.” He called “part of the training at [former segregated, all-Black] St. Philip Hospital “unbelievably primitive and dehumanizing.” Looking back, he wrote, “Now I am sorry that I was not more proactive” about speaking out about what he saw. “Thank you so much for writing this book,” Bernie wrote. “It has taken 50 years for me to finally face the real systemic racism at that time.” Dr. Bill Crouch, a retired cardio-thoracic surgeon from Colorado Springs, Colorado, offered a different perspective. “Recently read and enjoyed Organ Thieves,” he wrote. “I, along with 5 of my peers, were surgical residents at MCV during this time. Have communicated with each of them about the book, all either read or reading now.” Crouch reported that he was initially put off by what he called the “incrimination of Hume & Lower, two of our ‘heroes’ at MCV. As I got deeper into the book I was so impressed by the research and assimilation of information about this time, even without trial documents.” Speaking of his peers, he continued, “Your book has given us the opportunity to re-connect after many years and to reminisce about life as poor, overworked surgical residents. We all feel that although we had miserable hours, we probably had as much fun at MCV as in any of our subsequent practices. There was a wonderful esprit there among the surgical house staff to a great extent from the charisma of Drs. Hume and Lower. “ “I think the only facet we disagree on is the discrimination of blacks at MCV during the ’60s. We all felt indigent patients got as good, if not better care, than private patients. We, as house staff, cared for them diligently around the clock.” Regarding the book’s assertions about the hospital’s anemic attempts to contact the family of Bruce Tucker before removing his heart and kidneys without any prior consent, Crouch said he and his peers “felt attempts at notification of Bruce Tucker’s family were all that could be done… The urgency of time applied to this decision.”  A major West Coast bookseller -- Powell’s City of Books in Portland, Oregon – has The Organ Thieves on its holiday “What I’m Giving” list. “Since nothing says ‘I know you’ more than a carefully selected book,” the nationally known merchant explains, “we're sharing the top 22 books we're giving to our friends and family this holiday season.” Powell’s, which calls itself “The World’s Largest Independent Bookstore,” provides witty takes on each gift. Here’s the entry for The Organ Thieves: To: “My med student cousin, who got the whole family to read The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” From: “Your proud, ethics-board-obsessed cousin.” Powell’s City of Books offers other suggestions for your reading or gift-giving needs. From Oregon we move to Texas, where The North Dallas Gazette recently opined, “Though this is a nonfiction book, fans of medical thrillers will devour it. Readers who love true medicine stories, history, and courtroom drama will love it, too…” Lastly, check out this incisive interview on Radio Health Journal, which noted “how incidents such as this help to explain ongoing African-American distrust of medicine.” . The Washington Post had an excellent review in its Sept. 26 “Health and Science” section. Though The Organ Thieves “was written before the disparities of covid-19 and George Floyd’s death,” Erin Blakemore writes, “the abuses it records are decades old.” She also said that “the gruesome disregard for Black lives it documents makes it an urgently modern warning.”

Click here for my recent essay in the History News Network, an online publication of The George Washington University’s Columbian College of Arts & Science. Finally, here's an insightful letter to the editor in the October 10 Richmond Times-Dispatch, “VCU should honor Tucker for role in medical history.” Reader Robert Morrison of Midlothian, Virginia urges the university to embrace Bruce Tucker in its ongoing efforts to apologize for past wrongs and to correct mistakes in its official narrative. "Editor, Times-Dispatch: In their recent op-ed, University of Richmond School of Arts & Sciences Dean Patrice D. Rankine and anthropology professor Rania Kassab Sweis speak of 'universal sacrifice,' the need for yet unproven, sometimes harmful clinical medical trials. Participants 'have often come from Black and/or underserved communities, and their bodies have been used in the name of science, sometimes without their full and informed consent,' say the authors. Lack of informed consent happened at now-VCU Medical Center, according to Chip Jones in his recently published book 'The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in America's Segregated South.' For the transplant, neither Black 'donor' Bruce Tucker nor his family gave consent. In his well-researched history, Jones’ page-turner chronicles the wrongful death and negligence suit against then-Medical College of Virginia (MCV), lost in large part on a controversial change of heart in a crucial judicial ruling. Jones also explores MCV’s complicity in earlier 20th-century grave robbing, mostly of Black bodies, for cadavers for medical research, and of a 1990s hasty decision to stop archaeological research and cover up an old cadaver 'bone pit.' Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) has turned the page on many of its former practices that suggested Black lives didn't matter, and a VCU-formed descendant community group has begun advocating for studying and memorializing of exploited people, 'to restore and bring them the dignity they deserve,' writes Jones. But 'to date, no one has reached out to Bruce Tucker’s descendants.' Moving forward in racial reconciliation, trust is crucial. With Virginia’s long history of race-based privilege and discrimination, building trust requires no stone left unturned in honestly facing and publicly acknowledging regretted history. VCU should reach out to the Tuckers. It should honor Bruce Tucker, who helped make medical history. We should expect it." I look forward to seeing more letters from insightful readers like Robert Morrison. Stay tuned for more reader comments about the book along with breaking news about The Organ Thieves! Autographed copies are still available from Chop Suey Books in Richmond. |

Chip JonesChip Jones is an award-winning author, journalist and former communications director of the Richmond Academy of Medicine. The Organ Thieves is his fourth book. Archives

October 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed